The Majestic Mount Fuji

Mount Fuji is the absolute symbol of Japan, found in art, customs and everyday life. Its symbolism goes even deeper, as it represents the interaction between man and nature. It is a sacred volcano, a Shinto divinity and best appreciated from a distance, when covered by snow.

An exhibition at the musée Guimet in Paris showcases a precious collection of prints, with Mount Fuji, the snow, or both, as their theme. It is also worth visting the Guimet museum, a world reference in Asian arts. Emile Guimet was one of the first Europeans who traveled to Asia, studied and collected religious objects. Far East was an unexplored land, and Guimet, like some few others of his contemporaries, took the first step towards the understanding of these mysterious civilizations. He donated his collection of artworks and books to the French state and financed the construction of the museum that bears his name. Guimet would become the most important collector of Asian art outside Asia.

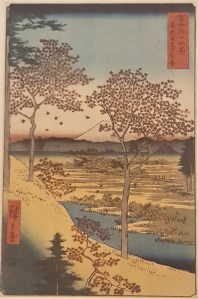

Fujisan, as it is affectionately called, has inspired many artists and poets. Since the 19th C, it is considered an international symbol, easily identifiable, with a profound influence in Western culture. The arrival of Japanese prints in Europe in the mid 19th C, allegedly as wrapping paper for the porcelains much appreciated and collected by the connoisseurs, shook profoundly the Western esthetics. Europeans discovered a new approach, very different to the principles inherited from the Antiquity and the Renaissance. Westerners discovered an art with no symmetry, no perspective, no rendering of the third dimension, no precise anatomy and yet poetic, expressive and respectful of the world around us. The figure of the mount Fuji was a recurrent subject matter that fascinated artists and art lovers who discovered the weather phenomena, like the wind, the rain, the tempest or the snow, represented in all their simplicity and majesty.

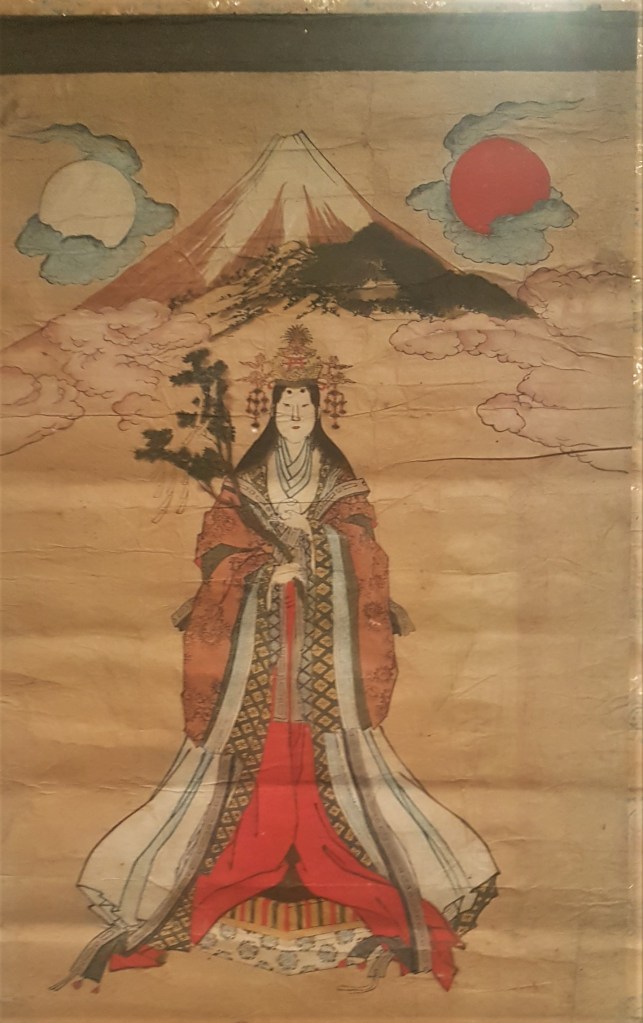

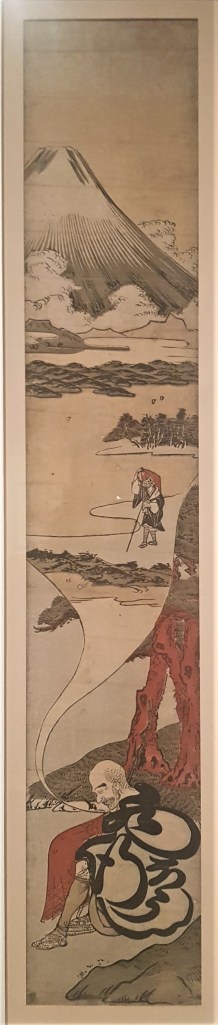

Woodblock prints were developed in Japan from the 17th C. onwards, but painting existed long before; the first representations of Mount Fuji are dated in the 9th C. Its summit and slopes are populated by gods and spirits, while shrines all the way to the top make it a sacred pilgrimage site. The goddess Konoha Sakuya Hime depicted above, is the blossom-princess and symbol of the fragile life but also the goddess of all volcanoes, including Fuji.

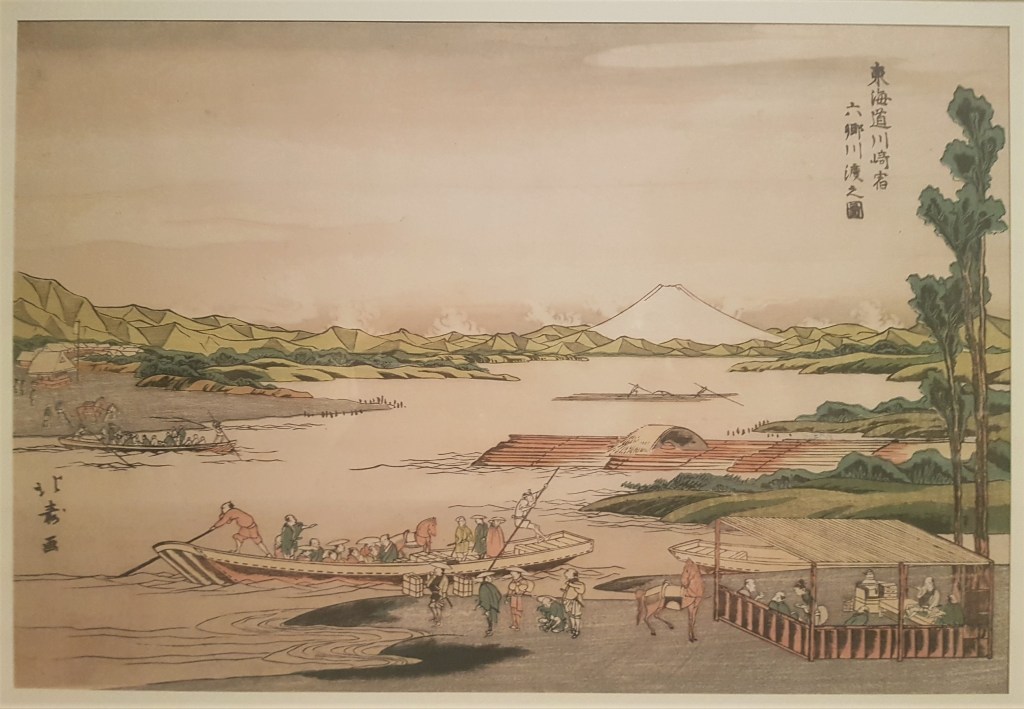

The Edo period, named after the capital of the Shoguns (modern Tokyo), lasted two and a half centuries (1603-1868) and brought stability but also seclusion. Japan became a closed country, no one was allowed to enter or exit under punishment of death. An urban society of merchants was developed due to the economic growth of the main cities, along with their own culture of pleasures including theatre, tea ceremonies, sumo wrestling and woodblock prints. Woodblock prints, called ukiyo-e, literally translated as images of the floating world, depict the society’s pleasures, from actors and geishas to travel scenes and landscapes. In the print above, Mount Fuji appears in the dream of a monk, and dates from the early period when nature featured in art rather as the background than the main theme.

Affordable and readily available, those images became extremely popular, with a peak at the end of the Edo era, due to the works of the two most famous artists: Hokusai and Hiroshige.

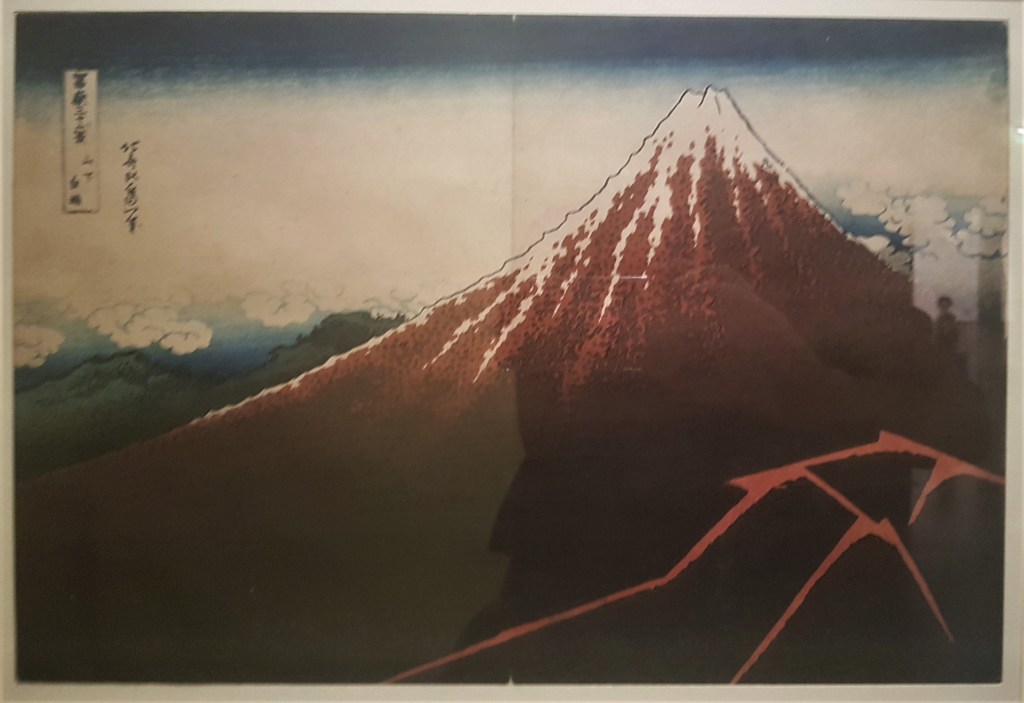

Hokusai is one of the greatest, and certainly the most famous and prolific, ukiyo-e artist, with a total of 30 000 works produced. Active at the end of the Edo period, he was the artist who created landscapes without the pretext of human action. A few prints from his masterpiece 36 views of Mount Fuji (in fact it contains 46 views) are on display. The print of The Great Wave off Kanagawa, the great star of this series, is part of the Guimet collection, but already presented many times and thus not included in the exhibition. That’s good news, because we can discover some lesser known pictures, like the impressive Rainstorm beneath the summit.

Hokusai consecrated this series to Mount Fuji because he was obsessed with this absolute symbol of nature, immortality and the Buddhist notion of impermanence He used to travel a lot and he was capable to draw the volcano from different spots in different seasons. His intention was also commercial, aiming to satisfy the increasing demand for travel views.

Another masterpiece by Hokusai, depicts the perfect shape of Mount Fuji in the simplest manner and in perfect balance with the cloudy sky. The title specifies the fine, or south, wind of early autumn, and indeed, on sunrise, Fuji turns red. The colours of the sky are reflected on the slopes while the first snow crowns the top.

Another impression of the Red Fuji on display is the variant in blue, where the clouds occupy a smaller portion and the picture fully demonstrates the force of the initial design.

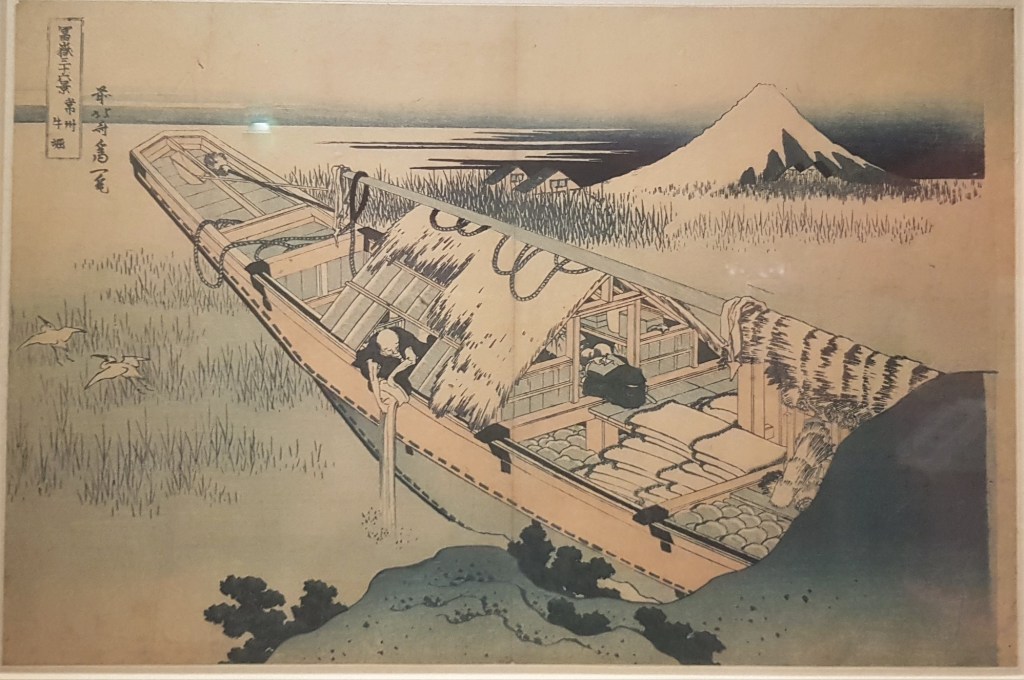

Two more of Hokusai’s 36 views of Mount Fuji depict the volcano as the background to a story, illustrating its multiple facets in the Japanese consciousness.

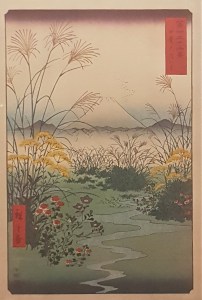

Mount Fuji is visible from many locations and features in the background of various compositions as an element of the landscape. The goal of the artists is not a faithful rendering but rather the acknowledgement of its presence and a way to pay their respects. Hiroshige, the last great master, contemporary and rival to Hokusai, produced a more figurative, colourful and narrative art, with humans, animals and plants occupying a prominent place, while Fuji in the back is putting each scene in context. He also produced his own 36 views of Mount Fuji, a generation after Hokusai.

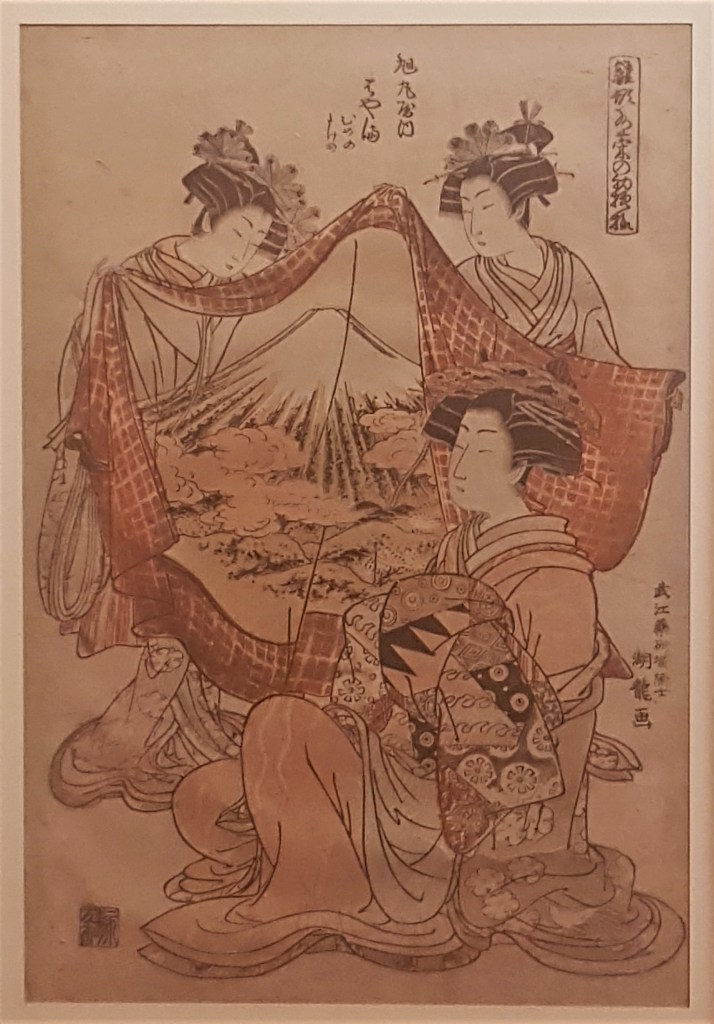

The exhibition also explores the presence and meaning of Mount Fuji in other kinds of compositions. For instance, in the print above, a group of courtesans admire the latest fashion, entirely gracious and pious towards another fundamental Japanese art, textile printing, with a fabric sample featuring Fujisan as a motif.

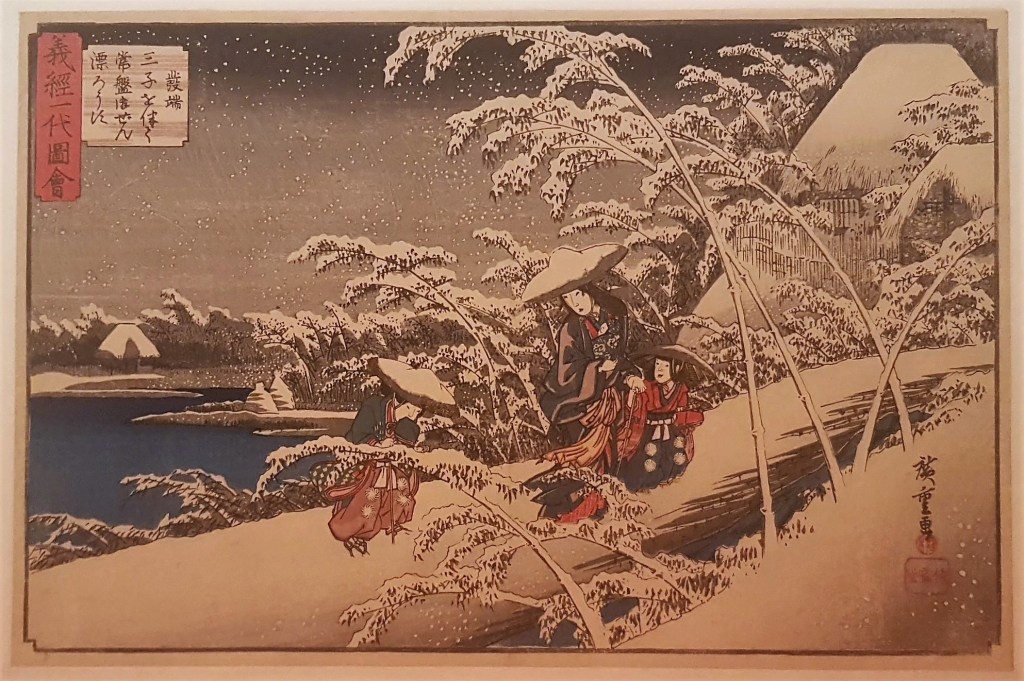

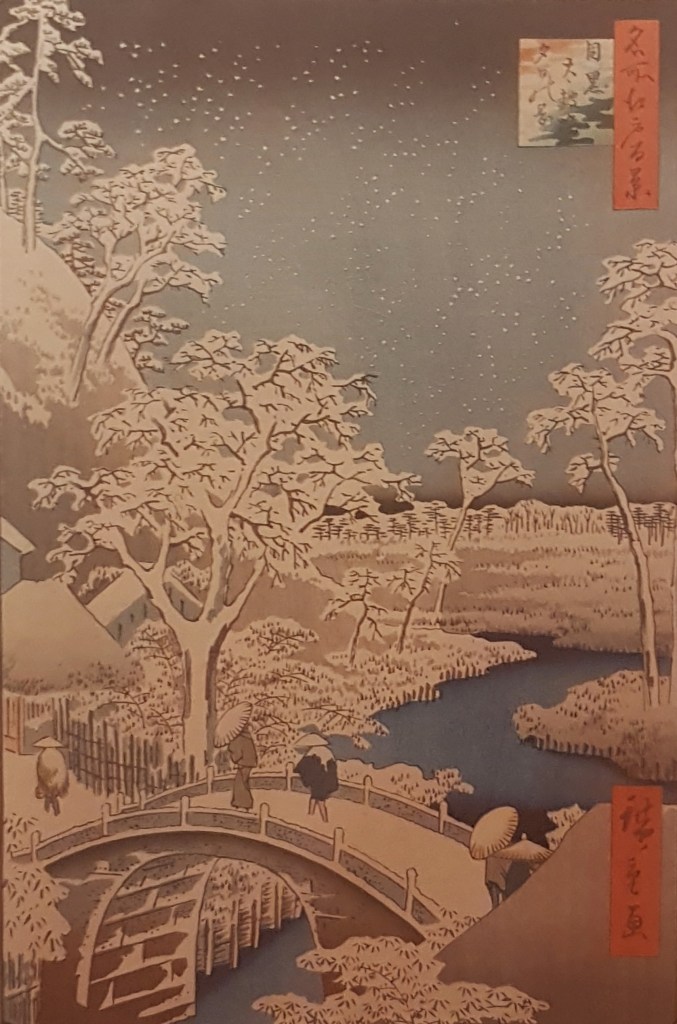

The exhibition includes snowscapes in Japanese prints beyond Mount Fuji. In this section, humans are confronted to the harsh winter conditions, challenged by nature, always in self-restrained, undramatic postures while the spirits are invisibly present. Some more pictures by Hiroshige are on display. Although relations were not established yet with the rest of the world, Hiroshige had access to some rare art books imported in Japan. In the landscapes above it is interesting to observe an attempt to apply the rules of perspective. At the same time, technique-wise, the artist fully exploits the whiteness of the paper making it the essential element of the composition. Europeans, once in contact with the Japanese prints, would discover the force of the void and emptiness. As a consequence, the overcharged art styles of the time will make way to the Impressionism and the Art Nouveau.

The period of seclusion came to an end after an intense pressure from the east and the west of Japan, as it was surrounded by superpowers, much more advanced industrially and militarily. Japan had to modernize and the following period, known as the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912), began with regular contacts and commercial treaties signed with foreign countries. During this period, the rejection of the country’s past and traditions was a side-effect. The quality of the woodblock prints declined, especially after the arrival of the new industrial printing techniques and materials, but also due to the increasing use of photography.

During the Meiji period, the production of woodblock prints aimed to satisfy the international clientele. Huge numbers of prints were available in the European market inspiring modern art, and vice-versa, Japanese artists sought to understand and apply the principles of Western art. Contemporary subject-matters are rendered with a combination of techniques from the two worlds, summed up as oriental simplicity and western effects of depth.

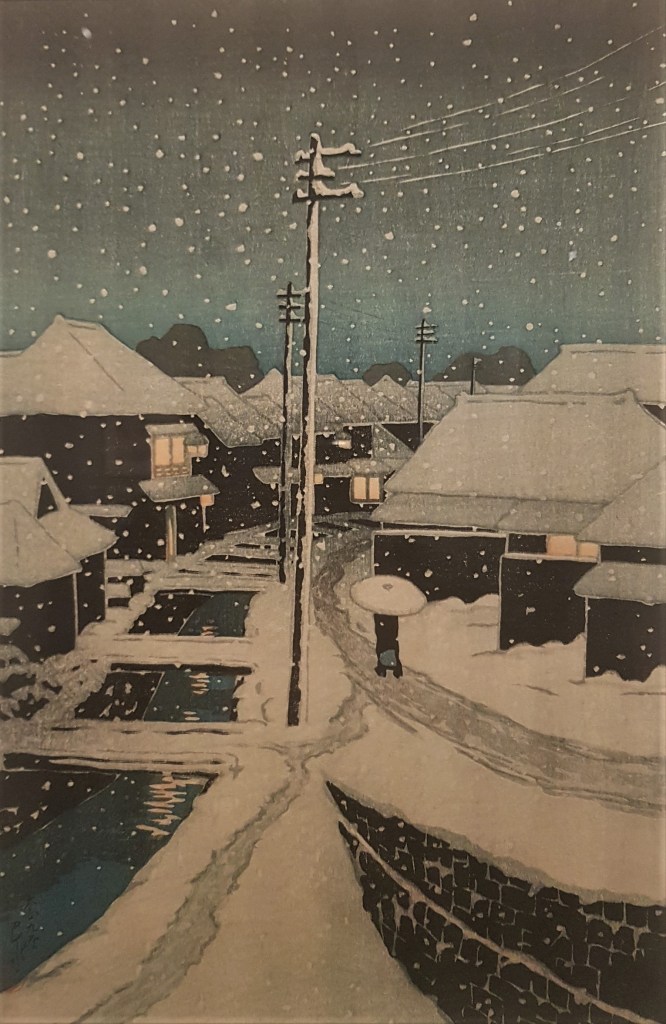

The Meiji era ended in 1912 and Japan progressively reconciliated with its traditions, especially after the humiliating defeat of the Second World War. An equilibrium settled, with an extreme modernity and a proud acknowledgment of its identity. In Hasui’s works, the great master of snowscapes in the 20th C, we can fully see this shift in the arts. In 1920, the perspective could not be more European, reflecting progress. 30 years later, and after the trauma of the war, the progress is still here, the figures are dressed fashionably. At the same time, the scene is dominated by an impressive and imposing red temple, while the snow washes away in silence the contrast to give birth to contemporary Japan.

Fuji, pays de neige, Musée Guimet, Paris, until October 12, 2020.

All images (c) The ChoiceOfParis