Before and After Cezanne_

Paul Cezanne marked the passage to Modernity and the 20th C Art. Close to the Impressionists, he took their vision further establishing a new link with nature, not by just exploring the effects of light, but by translating the mystery of creation into shapes and colours. Being conscientious of his researches, he always said that an artist is an independent maker who must find his own path, acknowledging, however, the debt he owes to his predecessors. Cezanne was a frequent visitor of museums, respected profoundly the great masters and processed their achievements in a very personal way. This exhibition suggests to appreciate his art through a different angle, exploring this continuity, or even fraternity, that exists among masters who share the same preoccupation: to seek the truth. Although he had an admiration for all great masters of the past and he deeply influenced the next generations (without him Picasso would have created a totally different art), this exhibition rather concentrates on his studies of the greatest of the Baroque and the Classicism, while for the period after, the display is limited to the production of the Italian Novecento proposing an additional viewpoint of his influence beyond the obvious one on Cubism and Abstract Art.

In the Marmottan-Monet exhibition, 60 works are on display. Cezanne’s works are hanging next to their source of inspiration. Nevertheless, he never copied or imitated those famous paintings. He had never travelled to Italy and rarely mentioned Italian art. Perhaps, the fact he never visited, allowed him to keep a critical eye and not fall for the awe of classical Antiquity and Renaissance. In addition, he had a sophisticated Italian culture, spoke Latin, knew his classics and later discovered Italian artists in the museums. Besides, Provence, his birthplace, offered the same natural setting and constant light, so Italy became a creative dream, hence the title of the exhibition.

By observing those masterpieces, he was capable to keep the essential, as he would do with his own pictorial compositions. The exhibition does not claim to precisely identify his inspirations, but rather to suggest a reconstitution of his artistic process. Cezanne and his friends, the Impressionists, had a very solid academic art background that allowed them to share the creative experience with their predecessors and head towards modern art. These artists bore the past, kept the essence and changed everything.

The pathos of Tintoretto and El Greco, visible in the works featured in the exhibition, is obvious in The Strangled Woman, where Cezanne paints a scene of extreme violence in a 16th-C-like dramatic composition and colourful chiaroscuro, previously employed for the Descent From the Cross.

The Murder is another image of violence, constructed by colour and depicting light reflections on complex surfaces, enhanced by the figure of the helpless victim. The whole becomes more dramatic by the diagonals, the strong primary colours and the emotion. Once again, the composition and the power of colour can be associated to Tintoretto’s The Deploration of Christ. Cezanne constructs images in sheer contrast to the dominating Academic Art of his times which produced paintings as copies of classical statues.

Although attracted by the Baroque emotion, Cezanne drew from Classicism the precision of lines, postures and gestures towards his quest for the truth of nature. In the two paintings above by Poussin, we find the same correspondence between human figures and natural shapes, organized in vertical and horizontal lines, with an opening in the middle that become only more obvious after having spent a few moments in front of Cezanne’s. Cezanne does not apply the geometric rules but he achieves a similar notion of depth. Here are two artists dealing with the outdoors; the first one establishing the “classic” notion of it, the second launching its “modern” aspect leading to Cubism. We could argue that Poussin’s paintings function as a perfect landscape that Cezanne is free to interpret in the same manner that the Impressionists paint in situ their impressions of natural landscapes.

Portraits represent a big part of Cezanne’s oeuvre. He was a tyrant during the sittings, his models were not allowed to move a finger, and he would need months to achieve a portrait. The legend goes that it took over 100 sittings for the portrait of Ambroise Vollard, his art dealer. Of course, portraits were not just a rapid capture of the model’s soul. Portraits were a pretext to explore human nature and its place in a wider context. Each brushstroke, seemingly fast, is very much thought and only adds to the character. The contrast in his mother’s portrait reminds us of the Baroque drama and yet she becomes so familiar and caring as her gaze wonders beyond the frame, perhaps in a protective way, as Cezanne always felt his mother was doing for him.

The mount Sainte-Victoire, overlooking Aix, would become an obsession for Cezanne. Since a young age, he felt curious about the earth sciences, especially geology. Minerals and rocks represented for him the absolute origins, well before life began. The mass of the mountain is also a reminder of God, as it rises to the sky. He began painting it after the death of his father in 1886. In his first attempts he sticks to the usual landscape principles, as resumed in Millet’s Classical Landscape, that he must have certainly seen when in Marseille . He would continue painting the mountain until the end of his life, analyzing it in a way that colour and shape overtook any other reference. His conclusions on rendering the mineral aspect of things, would be applied to other compositions like in one of his very last works, the Chateau Noir. Without any notion of perspective or depth, Cezanne dismisses Western art and comes up with a rendering like a geological stratigraphy that reinforces the contrast and the unison between natural and manmade elements. Next to it, the Landscape by Poussin demonstrates the interest of past masters in rocks, but only painted from memory and sketches with figures as a narrative pretext, but likewise in an opposing harmony with the environment.

Still lives are abundant in Cezanne’s work. This subject-matter is another excuse to juxtapose nature to handmade objects but also a way to control the violence and the drama of his other compositions. In one of his earliest works from 1860, Cezanne already chose carefully the best view angle of each object, while next to it we can only admire the single viewpoint of the composition by Munari, of an absolutely mind-blowing precision of details and textures. A kind of fullness and richness is common in both paintings. It has been very rightly said that Cezanne invented a modern classicism which characterizes his landscapes, still lives and portraits.

The Novecento artists occupy an important place in the exhibition. Boccioni, Carra, Soffici, Morandi, Pirandello aspired to his autonomy and freedom, but also to his researches beyond the subject matter, towards the depiction of something timeless, even eternal. The term Novecento was coined in 1923 to describe the return to order in Italy, after WW1, as a reaction to the war and to the pre-war art of the avant-garde, like Cubism and Futurism. References are numerous to traditional art, used as the vehicle to build a new world and obviously Cezanne was considered a pioneer, especially given his affiliation to earlier Italian art. According to them, he represented simultaneously Impressionism and Classicism.

Cezanne’s influence is fully appreciated in Morandi’s Still life, featuring the same horizontal aspect, the same banality of objects, the same almost monochromatic density, the same thick layers. In 1922, Giorgio de Chirico was mentioning “the metaphysics of the most common objects”, a notion easily applied to both Cezanne and the Novecento. Indeed, when Cezanne was recognized as a great artist at the end of his life, his admirers would insist on his talent to make us see common objects, like there is something new to discover, revealing the endless possibilities of observation. No wonder Picasso took it further and broke up the commonest of objects to suggest a new role for the two-dimensional surface: reveal all aspects and views.

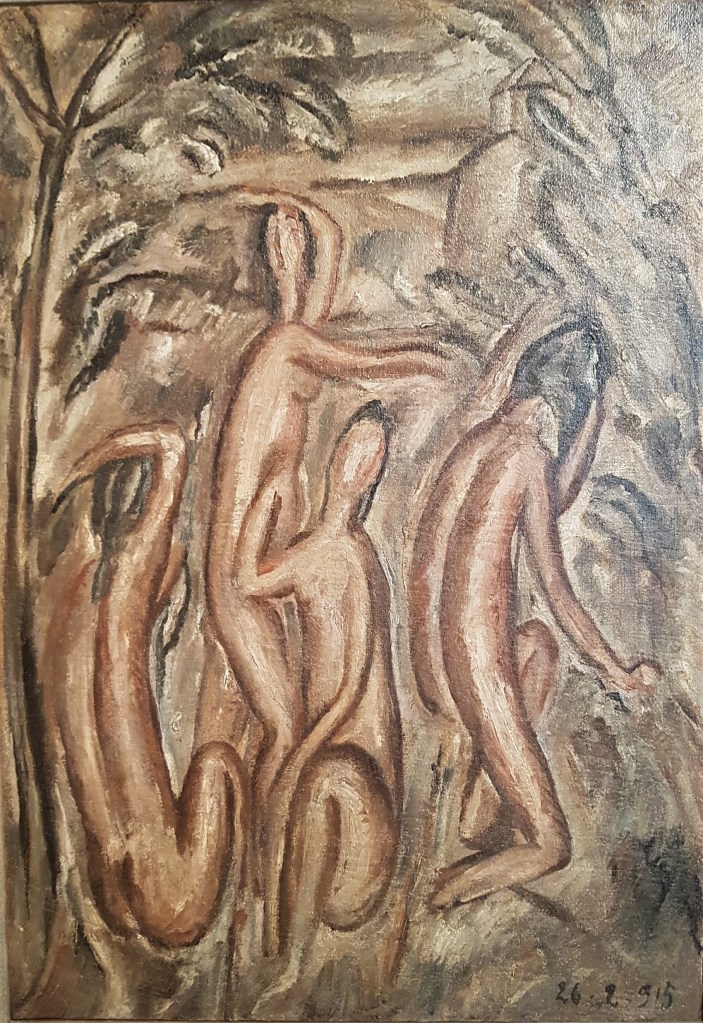

Finally, one of the great masterpieces sums up the achievements of Cezanne and his impact to the future generations. The Bathers are the antipode to nymphes, goddesses and all other names used for the nude. Manet shook conventions with the Luncheon on the grass. Cezanne took another route, equally groundbreaking: nudes in total harmony with their surroundings, filling up all the space, without any hint of their sensuality or femininity, becoming part of the mystery of creation. His nudes are not naked, just never dressed. The Novecento artists followed his steps, abandoning any mythological context, in order to produce this perfect unison, where human figures, trees, earth and sky become one.

Cezanne without breaking away from tradition, he innovated in the depiction of reality, sensations and impressions. He was one of a kind who influenced 20th C art beyond measure. Cezanne regularly payed tribute to the great artists of the past, like names not included in the exhibition, from Delacroix and Daubigny to his contemporaries such as Manet and Pissarro. It would be impossible to measure and display all the possible exchanges, and for this reason the exhibition manages to stay focused on Italy and reveal, this way, enough of his outstanding nature and production.

Cezanne and the Masters Painters – A dream of Italy, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, until January 3, 2021

All images ©TheChoiceOfParis

One thought on “Cezanne and the Master Painters – A Dream of Italy, Musée Marmottan Monet”