Drawings outside the box_

In Paris, we have been spoilt lately by museums showcasing drawings. In the Petit Palais we appreciated the fine arts drawings from the eclectic Prat Collection (see blog). The Musée des Arts Décoratifs is staging at the moment a different view on drawings: a mixture of fine and decorative arts, presented in a way that first and foremost is about enjoying the art of drawing as such. MAD Paris is a museum founded in the 19th C. to provide inspiration and models for artists, craftsmen, manufactories and industries, but also to cultivate the taste of a wider public about every-day objects. Drawings have always been fundamental in creation, either by materializing an idea, presenting different options, testing variations, convincing a client or as a record of the procedure. These drawings were not supposed to be exhibited, so already we feel like we are watching over the artsts’ back, and at the same time learning about the stages of making art or even about art never made or simply lost.

The MAD collection numbers 200 000 works on paper, covering different periods, styles, functions, techniques and destinations. Because of their variety, the curators took a risk, and decided to present 350 of them in an alphabetical order, outside chronological or stylistic contexts. The outcome is stunning as it appeals to all with an eye for the original. It would be too long to include in this post examples under all letters of the alphabet, but here is the choice I made:

A for Architecture. Architectural drawings really began in the 16th C. in France, during the Renaissance, as artists were discovering the ancient vestiges and copying them in order to create something new. Since, all projects have been conceived through drawings, and some famous buildings are exhibited, from when they were just lines on paper.

The “Pavillon des Renseignements et du Tourisme » by Robert Mallet-Stevens for the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, is an impressive work resuming the Art Deco and the modernism of its times. The purity and the austere geometry of the building is in striking contrast with the broad brushstrokes of the sky, the sketching quality of the passer-by, and especially the cubist rendering of a massive building in the background which, guess what, is the Grand Palais.

C for Créateurs. Creators, makers, craftsmen, artists and designers have been associated in different ways to the collections. A touching series of portraits in pastel by Charles Genty capture the moment of creating, like in this pastel portrait of René Lalique, drafting a motif inspired from flowers in his trademark style.

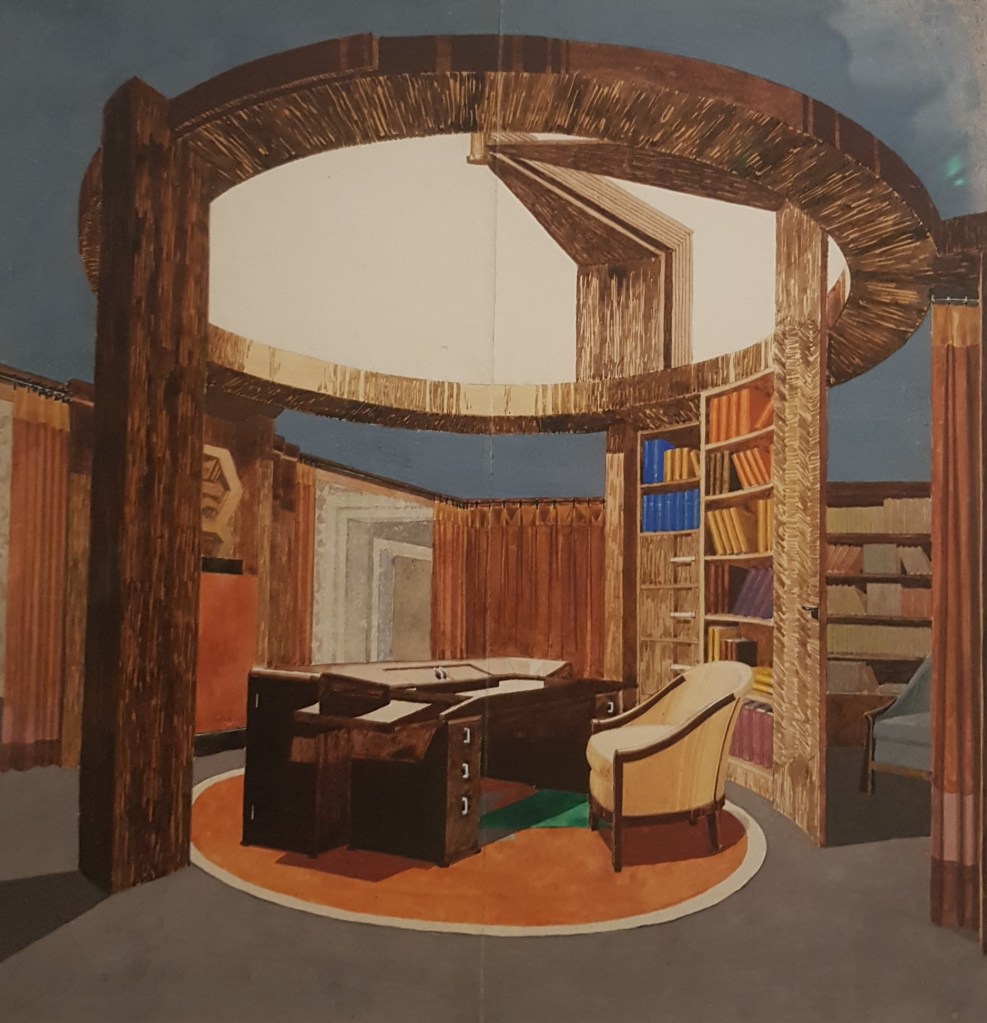

D for Décor, which is obvious for a Museum of Decorative arts. Plenty of drawings illustrate ideas, proposals, projects executed or rejected. Some famous names are on display, like Charles le Brun and Charles de la Fosse but also Italians, like Cherubini who made ceiling paintings for the Farnese family in Rome. The perspective and the tromp-l’oeil are perfectly outlined in this small drawing.

F for Figures. Portraits, group paintings and the human body have been subject matters treated by various artists at all times. An astonishing portrait, of Olimpia Pamphili is on display. It is a drawing not made as a preliminary sketch but as a finished work and it is one of 440 portraits of the 17th C Roman nobility made by Ottavio Leoni. He was obviously influenced by the portraits of François Clouet: the same size, the same intense gaze. Olimpia Pamphili was a very powerful woman as the sister-in-law and closest advisor to Pope Innocent X. Most of her portraits depict her as an ugly, ruthless woman, but here, in the earliest known portrait of hers, she is young, rather pretty and with a strong determination. The lines are delicate, her precious costume is roughly sketched while a light sfumato renders her hair very realistic.

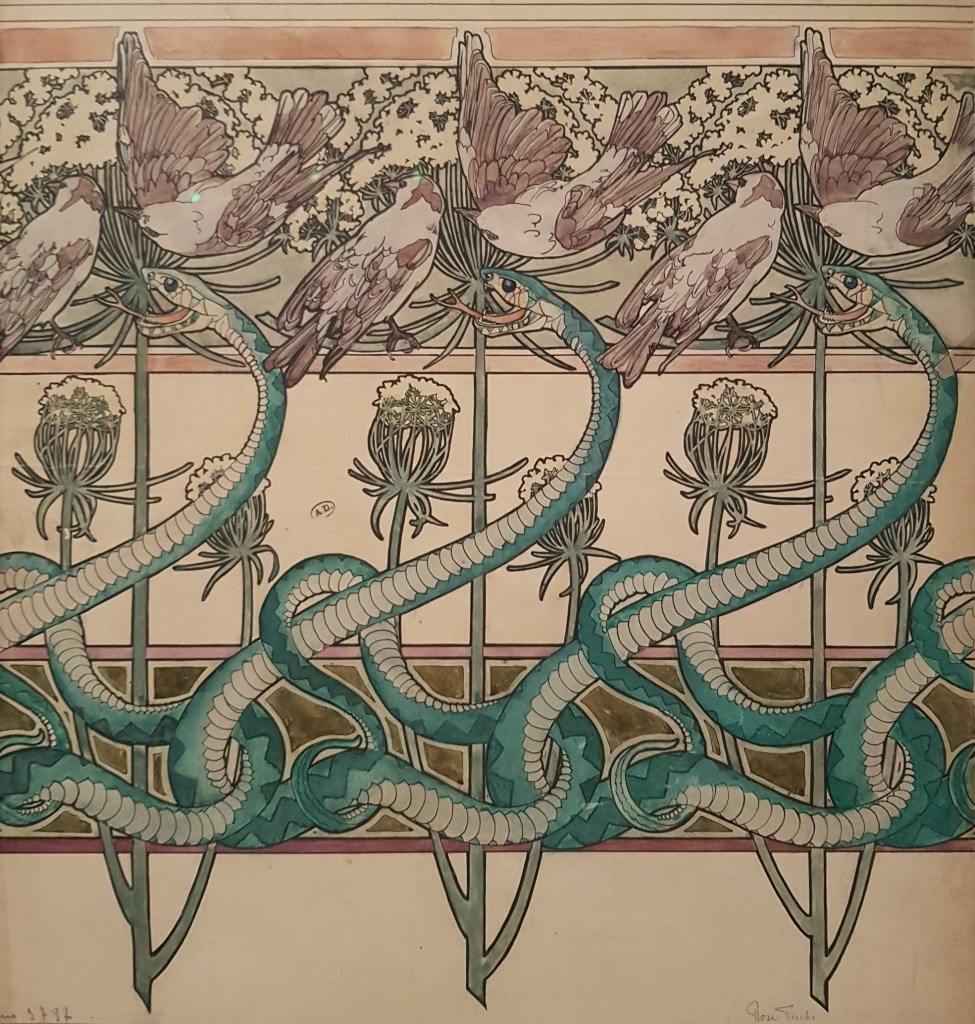

I for Impression, meaning prints. A beautiful drawing, in the Art Nouveau style, by Rosa Fuchs, a forgotten woman painter, illustrate the 19th C practice of commissioning artists to make plates of original patterns to be printed in books and catalogues as reference to contemporary makers.

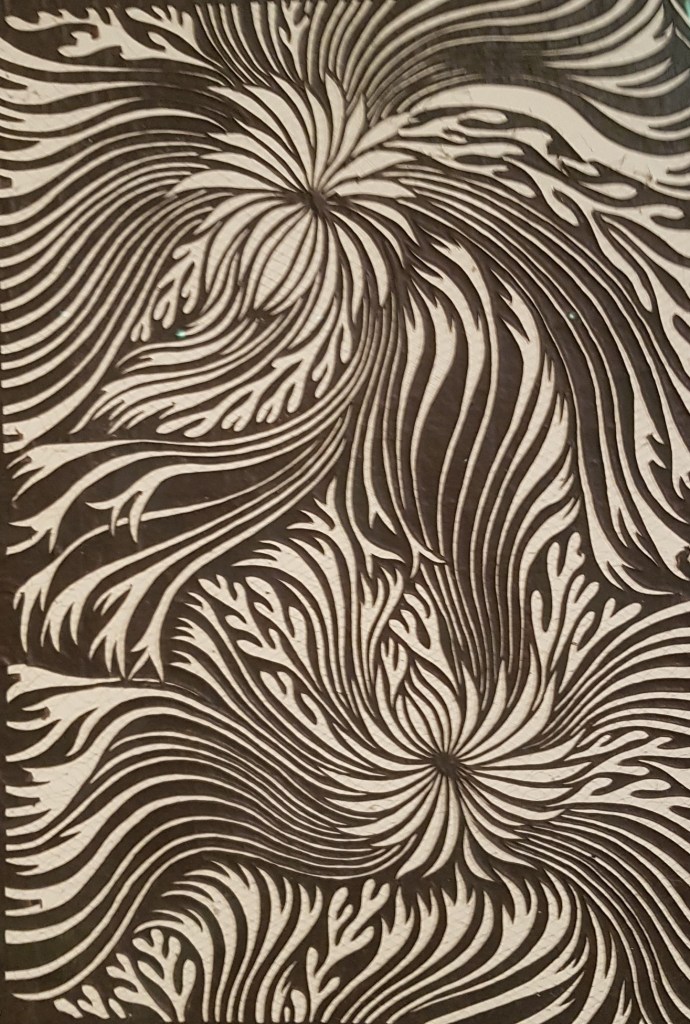

K for Katagami, the Japanese stencils or cut-outs in mulberry paper, for printing on textiles, especially kimonos. The variety is rich and the patterns surprise us with their modernity, even timelessness. Katagamis influenced all artists searching for inspiration in the decorative arts and they affected aesthetics in Europe along with Japanese woodblock prints.

M for Mobilier, or Furniture, which is abundantly represented in the MAD collections. One of the collection’s most famous drawings is a counterproof by one of the greatest French cabinet makers, André-Charles Boulle. In this drawing, Boulle sketched half of the piece, folded and pressed the paper, obtaining this way its mirror image. This method allowed him to work faster and develop variations of the original idea on the counterproof half.

P for Paysage, or Landscape. The exhibition features a series of watercolours by Henri Rivière, an artist influenced by the Japanese art, who applied its esthetics in the production of commercial posters. His landscapes are views of Bretagne, but in angles and compositions that offer a fresh approach to the depiction of nature.

S for Seduire, or to seduce. Fashion and jewellery drawings represent a very high percentage in the collections. A model for a pendant by Mucha illustrates the unison between fine and applied arts that was launched at the end of the 19th C, mainly due to the impact of Arts & Crafts and Art Nouveau. The female figure was a popular decorative motif and here it is perfectly adjusted to the shape of the pendant.

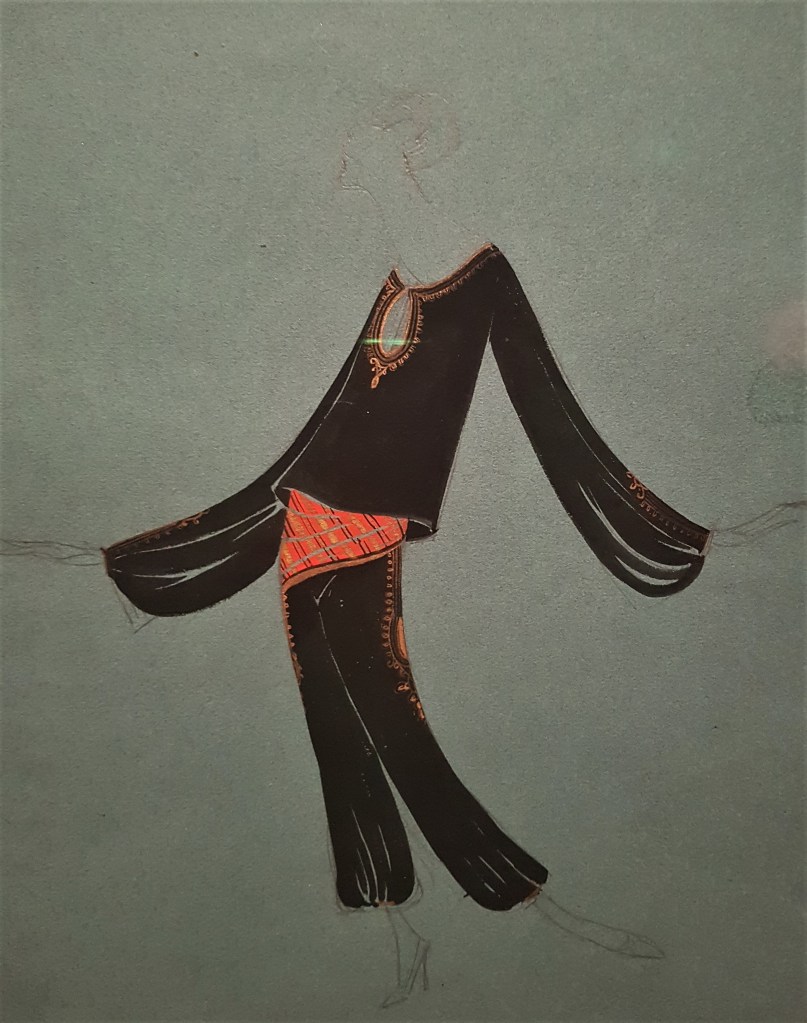

In the field of fashion, this exhibition introduces to the wide public a woman illustrator with a long and rich career. Marguerite Porracchia worked for 30 years for Jeanne Lanvin and in her illustrations, she captured wonderfully the aura of the modern elegant woman of the interwar period.

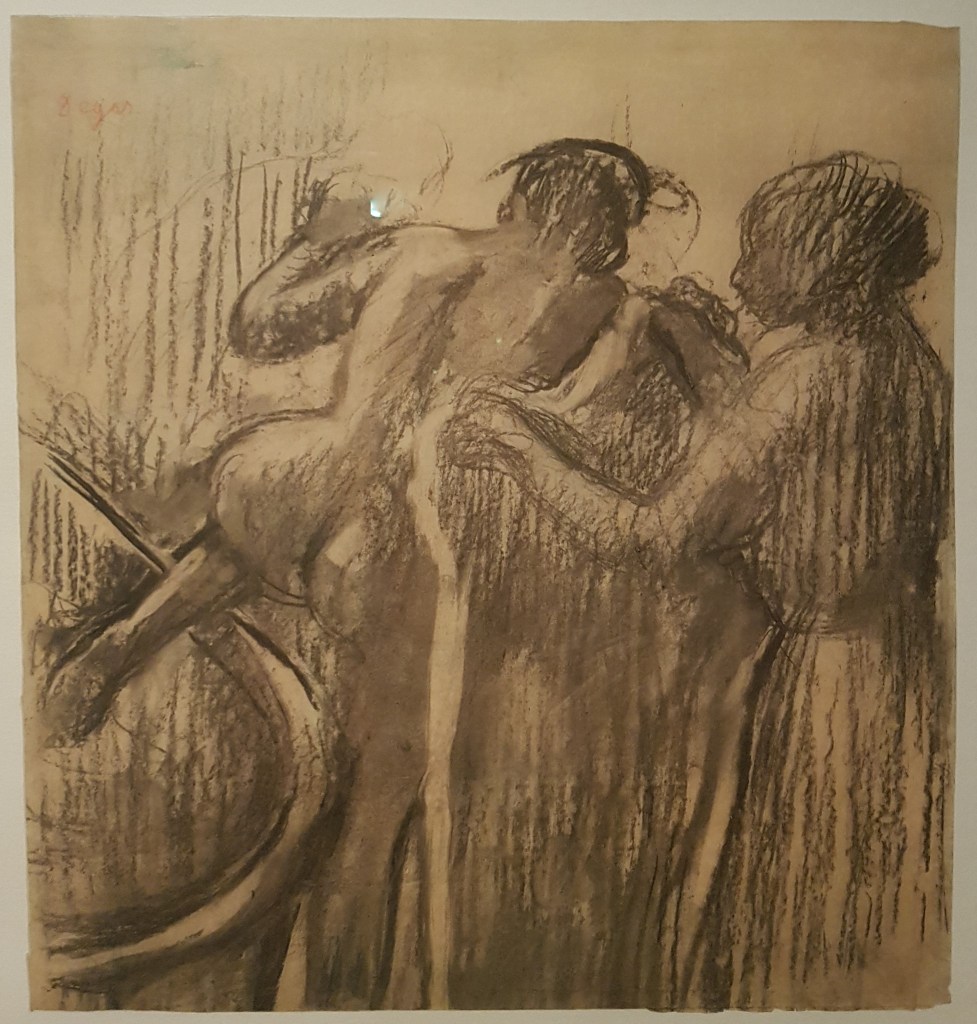

V for Vie Parisienne, or Parisian Life, that fascinated artists in the 19th C. Various drawings are on display of posters and theatre sets for the Opera, but undoubtedly the most striking is the “Sortie du Bain” by Degas. This charcoal sketch is one of his latest, on one of his favourite subject matters: the intimacy of women. The lines are quite rapid, the bather is very dynamic and the whole is balanced by the servant, totally solid, with almost straight lines to indicate her dress.

Drawings are a wonderful insight to the creative process. No matter how famous or not the maker is or has been, he shares with all the other artists the same quest for ideas, the same will to accomplish a project and the same questioning all along the process. In Le Dessin sans Réserve, all that is fully demonstrated and reveals an art that should not be seen as solely complementary to a finished work.

Le Dessin sans Réserve, Musée des Arts Décoratifs – MAD Paris, until January 31st, 2021.

All photos © theChoiceofParis