A prophecy from the past_

The Art Institute of Chicago

Giorgio De Chirico was one of those artists who challenged not only the meaning of painting but also art appreciation. The current exhibition in the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris showcases his early production, from 1906 to the end of World War I. This is extremely brief, especially for an artist who lived until 1978, and fans of his art might be disappointed. However, the curators wanted to put the accent on these years of metaphysical research that determined his later production, including his stay in Paris and his participation in the avant-garde. De Chirico spent 4 years in Paris where he developed the metaphysical painting, influenced André Breton and Surrealism, enjoyed a considerable recognition and mixed with Apollinaire, Picasso, Modigliani and Matisse.

Besides, the permanent collection of the Orangerie spans roughly in the same period, with artworks that had belonged to Paul Guillaume, De Chirico’s art dealer from his discovery to the late 30s. Paul Guillaume did own some paintings by the artist, which were sold by Guillaume’s widow, and thus this exhibition is an opportunity to find the missing link in his personal tastes.

Born in Volos, under the shadow of the mount Pelion, the country of the Centaurs, De Chirico was nourished by mythology. At the same time, he was in the center of modernity, as his father was responsible for the construction of the first railway. Ancient legends and industrial progress would become the primary elements in his artistic preoccupations, questioning all through his carrer the roots and the destiny of humans. Prometheus was painted in Munich, where he completed his art training and was introduced to German philosophers and German romanticism that provided the enigmatic dimension to his art. The rocky mountain is depicted in full majesty as an appropriate setting for heros, gods and nymphs, but the constructions show a different reality, mere mortals as its inhabitants.

Philadelphia Museum of Art

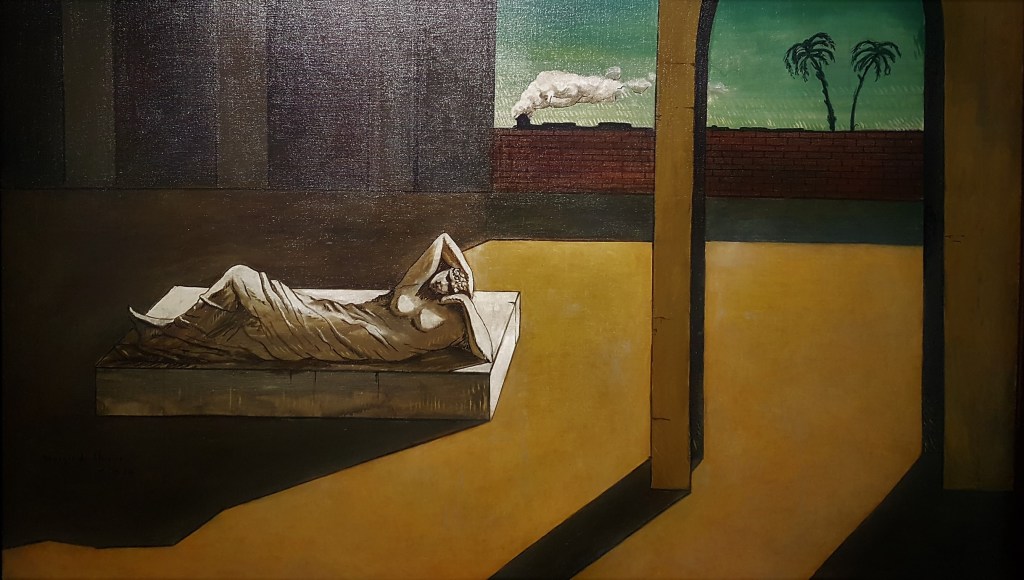

De Chirico was a passionate reader and follower of the philosophical theories of Schopenhauer, Weininger and Nietzsche. Ariadne, mentioned by the latter, is a figure frequently featured in De Chirico’s works. After helping Theseus exit the labyrinth and being promised to become his wife, Ariadne was abandoned on an island and became the wife of god Dionysus thus ascending to the status of the Olympian gods. A mythological tale with all the ingredients: heroes, monsters, divine intervention, passion, love, betrayal and catharsis. De Chirico would employ the statue of the Sleeping Ariadne as a reference to those notions, positioned in the middle of impossible cityscapes, with arcades reminding of Turin, the city where he sought the footsteps of Nietzsche. Trains and railways stations would feature from now on in unexpected contexts, a direct association to his own father.

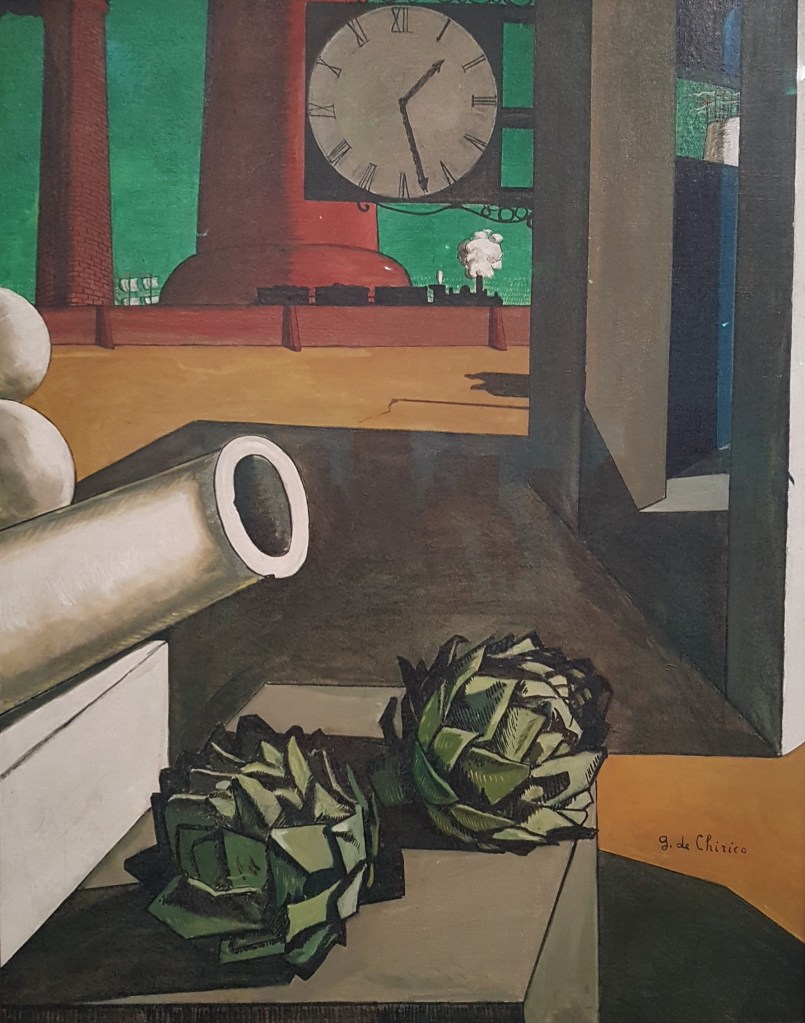

Recurring motifs would contribute to the elaboration of the metaphysical painting: trains, empty town squares, clocks, arcades, statues in improbable perspectives and banal objects, seeking to distill his own experiences and trigger doubts to the spectator. In the Pink Tower, a disturbing feeling of solitude is conveyed, enhanced by the disproportionate shadows, the empty arcades and the out-of-frame equestrian statue referring to a glorious and yet unaccomplished past. The dominant tower is the masculine counterpart of Ariadne and feminine symbols found in other works of the same period. A similar mysterious juxtaposition is depicted in the Philosopher’s Conquest, artichokes and a canon of a fallic conotation, the steaming train in the background, and a clock displaying the hour of the day when such shadows would be impossible. The accuracy of the rendering and the seemingly evident associations only widen the cleavage between reality and unconsciousness.

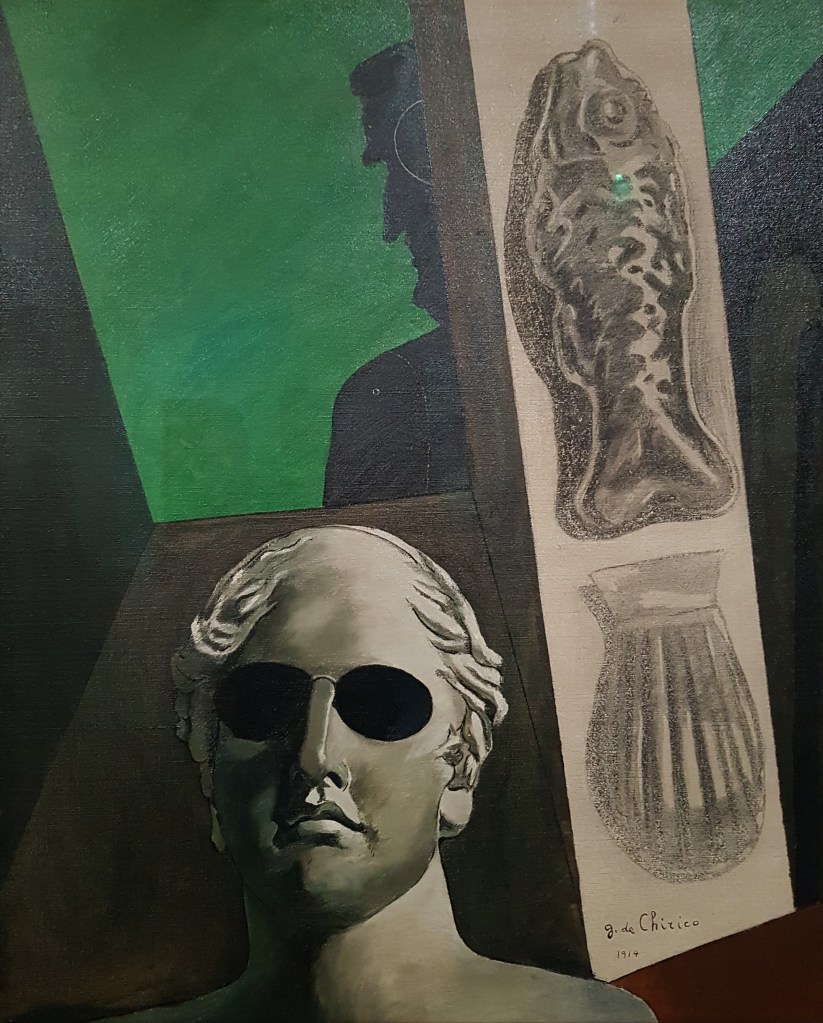

Guillaume Apollinaire discovered De Chirico’s art in Paris and coined the term Metaphysical Painting. They became close friends and shared free associations of objects and situations. Apollinaire wrote and published about his art, while De Chirico made his portrait, another variation of Metaphysical painting. The painter wanted to thank the poet for his reviews full of praise. The portrait was indeed received as enigmatic, as De Chirico had always wished, but Appolinaire did recognize himself in the background shadowy silhouette. Quite ironically, this figure bears a target on the left temple, where Apollinaire would be wounded two years later, hence the later addition to the title – prophetic – .

Museum of Modern Art.

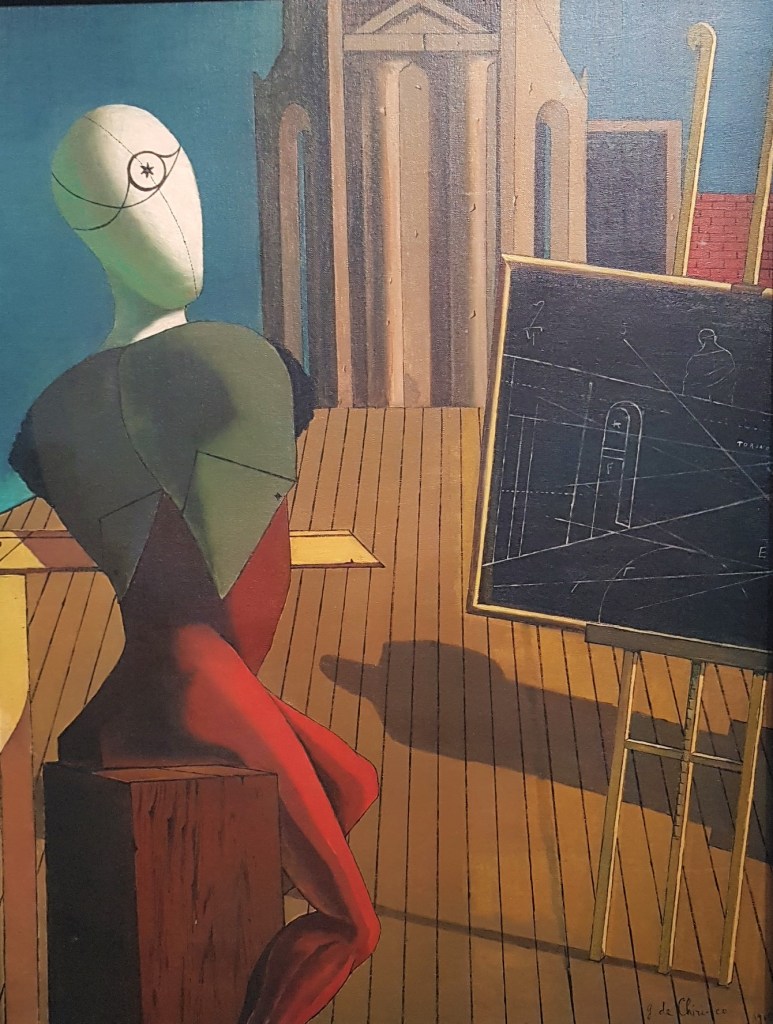

The Seer is one of his first works introducing the dummy, as an alter ego of De Chirico, who becomes the maker and the viewer of the painting. The multiple viewpoints are precisely indicated by the different kind of figures inhabiting the pictorial space: the single-eyed dummy, its shadow, a statue’s shadow, and the chalk figure on the blackboard.

In 1915, de Chirico was called to serve the army and returned to Italy, stationned in Ferarra for the next three years. He abandoned the disturbing cityscapes, perhaps because he found himself in this Renaissance town that, in a way, made his dreams come true, while the war materialized his worst nightmares. He focused on interior scenes with an extreme concentration of metaphysical elements, especially scientific and measurement instruments, alluding as always to the father figure. The madness of the war is behind the regular usage of mannequins during this period. At the same time, elsewhere, Abstract Art was introduced by Kandinsky who supported that figurative art could no more describe the atrocities of the war. De Chirico chose the mannequin to depict the same reality, employed as a symbol for the lack of soul, the loss of humanity and the wounded bodies coming back from the front. Allegedly, the first mannequin figure in his paintings was born out of the back of a chair used in electroshocks.

Chrysler Museum of Art

From the Ferarra period, his metaphysical paintings become interior views of overcharged compositions with every day objects. He also introduced optical illusions via the “painting inside a painting”, integrating views or objects within objects, creating this way an even more mysterious, suffocating, random situation. In the painting above, and as the title indicates, it is about homesickness, nostalgia for peaceful times, in the middle of a raging war. In the very center appears, majestic and over-dimensioned, the traditional biscuit of Ferarra turned to a reminder of the past, tradition and childhood.

In 1917, De Chirico met Carlo Carra in the military psychiatric hospital. Carra began immediately incorporating dummies in his works and shared the metaphysical vision of art advocated by De Chirico. The cruel reality was provided by the disturbing objects of the picture, for instance the rehabilitation equipment for the wounded. Carra’s Metaphysical period was short, following his Futurism and Cubism expressions, but it would lead him to a thorough analysis of ordinary objects.

Giorgio Morandi, a favourite of this blog, followed their lead in exploring metaphysical associations, he restrained however from the enigma, preferring instead to explore the “metaphysics of the most common objects”. The mannequin participates in the investigation of the essence of banality, soon to disappear from Morandi’s repertory, and give place to the pure and direct observation of the correlation between humans and nature.

Mario Lattes Collection

The exhibition ends with works dating from 1918, including some fine exemples of the series entitled Metaphysical Interiors. Crisp geometric constructions of familiar elements are painted in intersections and superpositions. The image challenges our existing memories and preconceived ideas as we are called to attribute a meaning. The realistic rendering enhances the plausibility of any possible interpretation.

De Chrico, sawed the seeds of Surrealism, that would fully develop after the war, integrating the subcontious and Freud’s theories. Nevertheless, he kept his distance from the movement whose leading figures likewise prefered to diminish the acknowledgement of his contribution. He would get occassionnaly back to a metaphysical expression only to make more complex any chronological study of his work. His art had always been about subjectivity and free associations, so he wanted to strip his legacy of any specific references.

The Orangerie exhibition successfully demostrates his input, but above all it invites us to give our own answers to the questions asked by De Chrico. Strolling through the rooms, we face a chilling similarity with our times: our world is as full as possible with familiar objects and yet a surreal, or even metaphysical feeling rules. We can relate to the solitude and anxiousness, claustrophobia and isolation that make us long for better days. The world nowadays, is even more an enigma, a puzzle with missing pieces that we can fill with our own resources. De Chirico fought through his life for the abolition of meaning in art. Today’s viewers should just follow his advice, forget about riddle solving or specifying contexts and let themselves engage in this call for insightfulness, from over a century ago.

Giorgio De Chirico, Metaphysical Painting. Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris, until December 14, 2020

All images ©TheChoiceOfParis